“Everything stretched out... it expanded!”

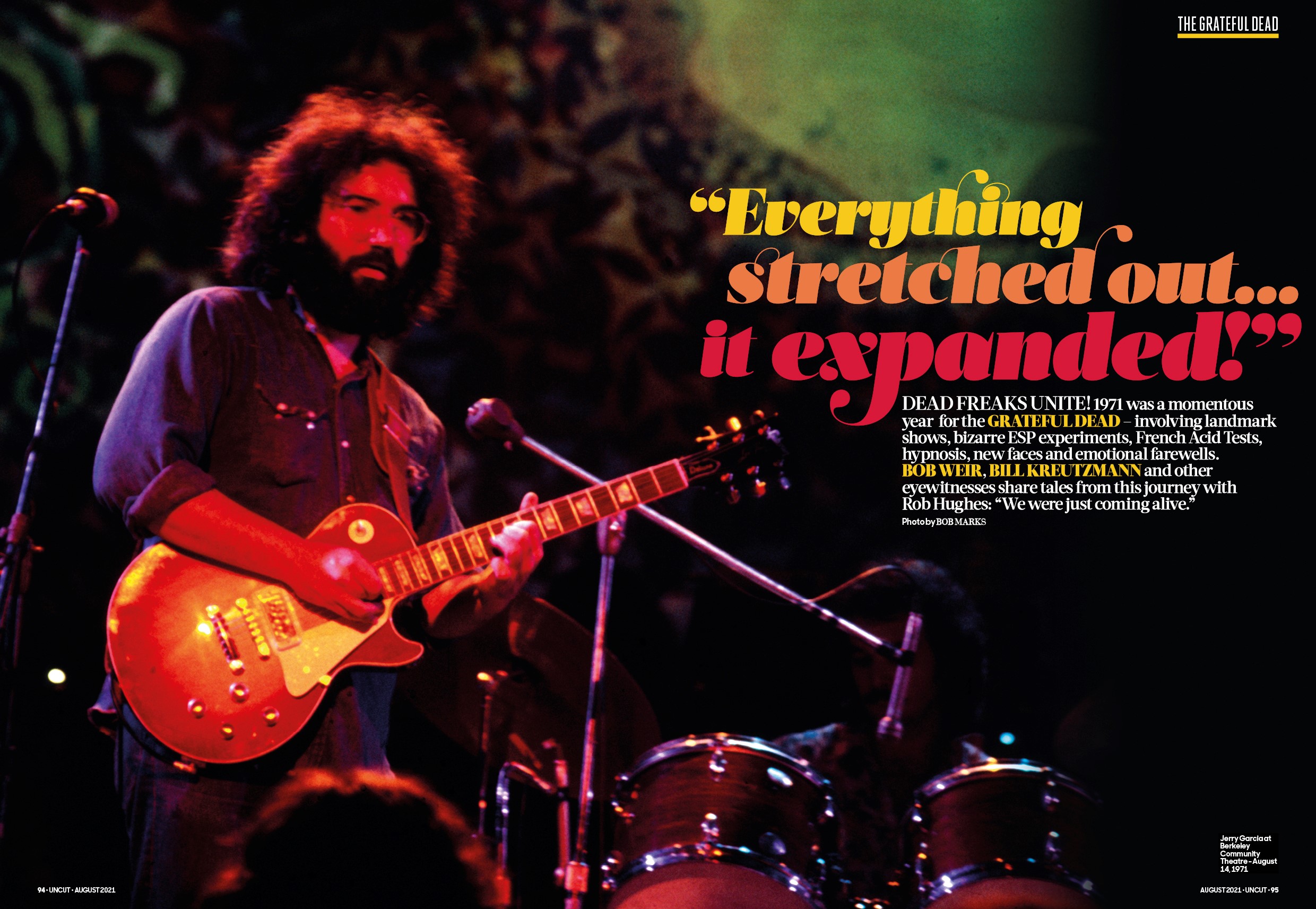

DEAD FREAKS UNITE! 1971 was a momentous year for the GRATEFUL DEAD – involving landmark shows, bizarre ESP experiments, French Acid Tests, hypnosis, new faces and emotional farewells. BOB WEIR, BILL KREUTZMANN and other eyewitnesses share tales from this journey with Rob Hughes: “We were just coming alive.”

The Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, some 30 miles north of NYC, began life as a pre-war cinema and vaudeville venue. By 1970, however, rock promoter Howard Stein had transformed it into a psychedelic pleasure palace. Traffic, Santana, Frank Zappa and Janis Joplin were among those who performed there that year – Joplin even premiered “Mercedez Benz”, written just hours earlier in a Port Chester bar – but its most regular attraction was the Grateful Dead.

The Dead found the Capitol crowd a little more attentive than at the Fillmore East, their other regular haunt on the East Coast. It was a place to stretch out, try different things, introduce new songs. The perfect venue, then, for a run of shows in February 1971 that heralded the next phase in their evolution.

“It was an incredibly creative time for the band,” recalls singer and rhythm guitarist Bob Weir. “We had the feeling that we’d basically opened up the bag and there was a lot more in there. We spent so much time with one another in those days, either on the road or at home, that we really learned how to play together. It all merged, at that point.”

On opening night – February 18 – the Dead chose to unpack a batch of remarkable new tunes: “Bertha”, “Wharf Rat”, “Loser”, “Playing In The Band” and “Greatest Story Ever Told”. Songs that became embedded in their live canon for years to come, shining illustrations of the band’s telepathic interplay, poised between limber melody and free improv.

Drummer Bill Kreutzmann remembers it as an exceptional period. “We were just really starting to become a band and those were really high moments,” he says. “We were just coming alive. All I could think about in those days was playing and getting to the show.”

In what turned out to be a profoundly transitional year that saw the temporary exit of founder member Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and Kreutzmann’s fellow drummer Mickey Hart, the band underwent a metamorphosis that involved landmark shows, bizarre ESP experiments, French Acid Tests, new faces and teary goodbyes. This shift was captured on double LP Grateful Dead (aka ‘Skull & Roses’ owing to its distinctive cover art by Alton Kelly and Stanley Mouse), the extraordinary live document of ’71, released that October. It’s the sound of a band pushing beyond themselves. Aside from its unique pyretic energy, the album illustrates the sheer diversity of the Dead: blues, country, psych, rock’n’roll, experimental jams.

“The band were better suited to the live environment than the studio,” says their trusted engineer Betty Cantor-Jackson, who co-produced ‘Skull & Roses’ with longtime cohort Bob Matthews. “Everything stretched out, it expanded. The music grew and grooved. It was amazing to be inside of that when it was happening.”

Crucially, too, the album expanded their reach. Until then viewed as a cult band who’d enjoyed a modest degree of success with their last two studio albums, Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, ‘Skull & Roses’ was their first gold-seller in American. The fan club callout on the album sleeve – “DEAD FREAKS UNITE: Who are you? Where are you? How are you?” – further galvanised a growing community of Deadheads that swelled to five figures over the next few years.

“In ’71 you’re looking at a hippie family turning into something else,” suggests pianist/organist Ned Lagin, a touring member of the Dead who also played on American Beauty. “They became far tougher and more lucrative. ‘Skull & Roses’ came out within that context of them being an entertainment/touring band rather than a counterculture art band. When I first saw the Dead in Boston two years earlier, they came out on stage an hour late, sat on their amps and tried to figure out what to do. By the fall of 1971 they’d filtered all of that out…”

dead comment

skull and roses

I was not into the GD in 71. My first real intro was probably 75 when a dorm buddy turned me into them. We listened to American Beauty, Mars Hotel, Workingsman Dead, Europe 72 and Skull and Roses. I still remember thinking and/or commenting that Skull and Roses was almost the history of American music...but not really. Frankly, it took me a while to fully appreciate the extended jams and spaced out improvs. I owe that friend a major favor for exposing me.

I was not into the GD in 71. My first real intro was probably 75 when a dorm buddy turned me into them. We listened to American Beauty, Mars Hotel, Workingsman Dead, Europe 72 and Skull and Roses. I still remember thinking and/or commenting that Skull and Roses was almost the history of American music...but not really. Frankly, it took me a while to fully appreciate the extended jams and spaced out improvs. I owe that friend a major favor for exposing me.

Thanks, dude fan. The story is certainly not funny