“Nooooooooooo!” I can hear my cry in a very hazy memory. April 2, 1973. The house lights dim, a roar builds steadily in the crowd and grows to a deafening din as the band members amble onto the stage at the Boston Garden. As the spotlights brighten, I squint from my perch near the top of the upper level of the enormous arena. Something doesn't look right onstage. “What the-?” Oh, my God, Bob Weir's ponytail is gone! Jeez, you don't see the band for eight months and all hell breaks loose.

Did it matter? Of course not! I'm mostly kidding, but in some way, the disappearance of that ponytail, which cascaded so elegantly down the middle of his back, felt like another sign that the band was leaving its hippie past behind and that young Bob, just 25 at the time, was—gasp!—growing up. I was about to turn 20 and wanted to be Bob Weir—not that I had an ounce of musical talent. But I dug the look and I loved what he brought to the Grateful Dead's unique chemistry. To me, he was the essence of hippie cool. My first Bob was the Cosmic Cowboy one; I'd missed the beautiful young androgyne by a couple of years.

Bob was the Wild One. He was the rock 'n' roller, but also the confident, smooth-voiced narrator on all those dramatic country-rock numbers about desperados and fugitives; a perfect fit for those tunes. He was the guy who would screech and scream himself hoarse at the end of the show, whipping us into a dancing frenzy. He was the droll, wise-cracking emcee informing us that the band would resume playing after technical gremlins had been extinguished and everything was “just exactly perfect.” In the early days, he even told a few bad jokes. What a prankster. Seems as though he was never far from a smile or a smirk.

Except sometimes when he was playing—then he'd often have that look of intense, focused concentration, as he conjured endless creative guitar lines that provided an ever-moving rhythmic center in the heart of the group's sound. Labeling him a “rhythm guitarist” always felt horribly inadequate, because he wasn't some guy just chopping out simple chords in a conventional pop music way. Rather, he used an immense musical vocabulary and deft touch to construct sophisticated parts that were both rhythmically assured and amazingly nuanced.

I have this picture in my head of him standing in a semicircle with Phil and Jerry in the early '70s blasting through the nether regions of “Dark Star,” or maybe “Playing in the Band,” and he's hunched over his big Gibson, his whole body in fluid motion, and you can practically see how the parts all fall together organically. One moment he's grinning at some miraculous turn the jam has taken, the next he shakes his head, flips the hair out of his eyes and looks up into the lights as if he's wondering where it can go next. I get excited just thinking about that dynamic interplay—that's what turned me into a Dead Head in 1970, at the age of 16, and what has nourished my soul ever since.

Of course there were also the songs, and Bob co-wrote many of my favorites from my first years seeing band—“The Other One,” “Jack Straw,” “Truckin',” “Sugar Magnolia,” “Playing in the Band,” “Greatest Story Ever Told,” “Mexicali Blues,” “Weather Report Suite”—all completely different one to the next, each a glimpse into a different world. Later, I was knocked out by “The Music Never Stopped” and “Estimated Prophet,” “Feel Like a Stranger” and the still-amazing combo of “Lost Sailor” and “Saint of Circumstance.” I got my early education in country music listening to Bob sing “El Paso,” “Mama Tried,” “Dark Hollow,” “Silver Threads and Golden Needles,” “The Race Is On” and “Big River,” and as time went on he provided new windows through which to view Dylan classics, old blues and so much more.

Basically, I'll follow him anywhere. I haven't loved every band he's been in or every song he's written. But he's earned my eternal respect and admiration for continually pushing boundaries and moving forward in a way that is so idiosyncratic—so … Bob!—that I want to be a part of and support whatever it is.

I first interviewed Bob for The Golden Road in the late '80s and instantly learned that what everyone in the Dead scene had told me through the years was true: he's a sweetheart! (It's a word you hear applied to him by both men and women.) He's warm, friendly, thoughtful, possesses a dry wit and has a surprisingly good and detailed memory (a boon to those of us who pester him with historical questions). I've never seen him be anything but polite to those around him, and in the dozen or so interviews I've done with him in the past 20 years—some on the phone, most in person—he has never really spoken ill of anyone. Which is not to say he lacks opinions or is uncritical. But he tends to give people the benefit of the doubt and he seems to have an inherent faith that things can and perhaps will work out for the best. His track record for giving his time unselfishly for benefits speaks for itself—and to his optimism.

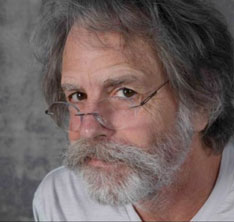

On his most recent birthday, October 16, Bob hit 65, retirement age for many. His bushy grey-white prospector's beard almost makes him look his age for the first time (when The Warlocks started, he was 17 and looked about 14; in his early 40s, he looked 10 years younger), but fortunately for all of us he has not slowed down one bit. Maybe he's just trying to keep up with his GD elders—that indefatigable wonder of nature Phil (72), Mickey (69) and Bill (66). Nah, he just loves his job. Playing music is what musicians do. Age is just number (says the writer, pushing 60).

Look at just some of the great work Bob has done the past couple of years: Multiple tours with Furthur; his extraordinary collaboration with the Marin Symphony; a handful of shows with RatDog (here's hoping for a RatDog tour in 2013!) and Scaring the Children (with Rob Wasserman and Jay Lane); fine music from his acoustic trio with Chris Robinson and Jackie Greene; a bunch o' solo shows, plus appearances with Bruce Hornsby and Branford Marsalis; and sit-ins with such disparate acts as 7 Walkers, Jackie Greene, Slightly Stoopid, The National and God Street Wine. Those last few were at Bob's magnificent high-def audio-video facility in San Rafael, Calif., TRI Studios. Bob has been extremely generous in sharing TRI with a broad spectrum of different artists, and is helping to pioneer a new era of high-quality music distribution over the Internet.

So here's a virtual toast to Bob on this auspicious occasion. You've done more for us than you'll ever know, and we're all counting on being able to celebrate 70, 75 and beyond with you! I know this song, it ain't never gonna end!

Care to share some nice thoughts/memories about Bob Weir?